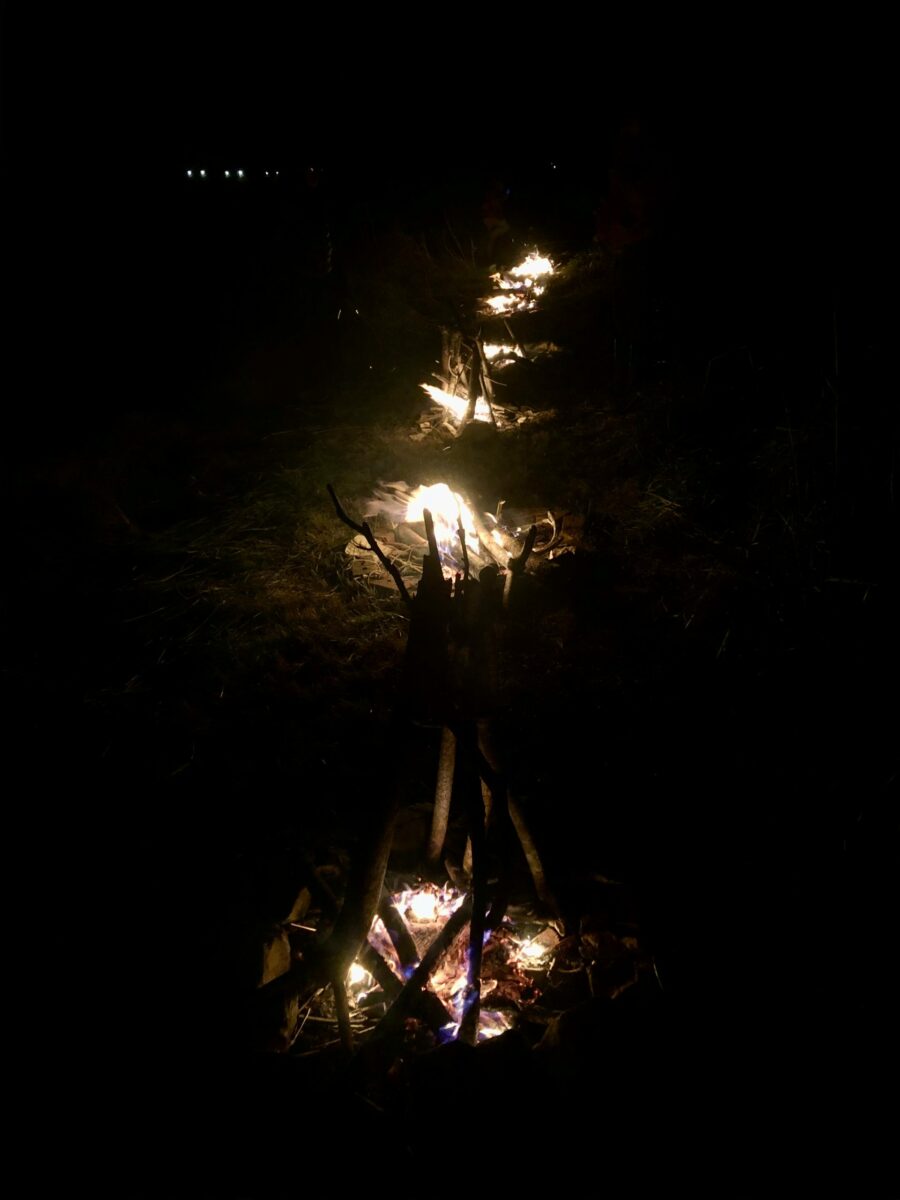

I’m standing before a row of blazing fires, eight of them, each encircled in rocks from the land that I helped guide into small protective circles. The fires are inviting, bright, warm, and noticeable. The fires make me feel safe in my body, held in a web of ancestral remembrance, and in awe of the wisdom Earthly elements can provide. We’re singing songs about the gift of Divine light in moments of darkness, opening ourselves up to the possibility that our suffering and joy and pain and celebration can all exist at once. I look into the fires and see all those who came before me staring into the same flame on the same night on the same new moon singing the same prayer. Hanukkah is a homecoming.

The journey of me arriving to this moment feels ancient– and it is. My ancestors brought me here through centuries of loving Judaism, fleeing Judaism, assimilating, forgetting, remembering, reclaiming, and restoring. I hold their stories in my bones and breath. The journey of me arriving to this moment also includes the events of my own lifetime, which encapsulate a mirrored sequence of fleeing, assimilating, forgetting, remembering, reclaiming, restoring, and especially *redefining* my relationship to Judaism.

The fires are telling me they can hold it all: the messiness, the abandonment, and the mistrust of my lineage. It’s okay to be in a process of learning where I come from. The fires are also reminding me that connecting to Ancestors/Source/Divinity/God/Creatrix/Magic happens in the presence of others doing the same work. The other humans nurturing the Hanukkah fires with me come from Yesod Farm+Kitchen, a majority queer and Jewish community space stewarding 16 acres of ancestral Tsalaguwetiyi and Catawba land near what some call Asheville, North Carolina. The folx here focus their energy on reviving earth-based Jewish ways of growing food, sharing prayer, and redistributing wealth and resources. The eight Hanukkah fires were a manifestation of all this, and I continue to overflow with gratitude that I was able to take part in a piece of the magic that happens here on this land.

I came to Yesod seeking answers to a long list of questions about what it means to be Jewish– What does it mean to be Jewish and a white settler on occupied Indigenous lands? What does it mean to come from diasporic peoples? Is there space for me in Judaism to pray to a feminine and genderqueer Creator? Why is it important to retain and restore the cultures and traditions of my people if they have been complicit in violent and colonial histories? Why should I love Judaism if patriarchy and white supremacy seem to be so deeply embedded in the religion I grew up practicing?

I’m in a slow and lifelong (generations long?) process of exploring these questions, and I exhale in body and soul knowing that there are places like Yesod and the allied Jewish Farmer Network, both projects co-founded by Yesod land steward SJ Seldin, to hold folx, young and old, in the question-asking. I accept that many, if not all, of these questions do not have clear answers, and I also accept that the shame, confusion, and intergenerational trauma that arises in the question asking is a necessary component of doing this healing work.

As a white person living in this so-called country benefiting from intergenerational wealth and the safety afforded to my family because we look the way we do, it feels imperative for me to both release the harmful practices of my ancestors and uplift the healing blessings, rituals, and values that they have carried with them.

Retaining and restoring the practices of my people nourishes me and eliminates a desire to steal or appropriate the traditions of others.

When I show up in my life as a land-steward and accomplice in the liberation for BIPOC, queer folx, differently abled folx, and so many others, I’m learning to call myself in to show up fully as white, Jewish, anti-Zionist, land-based, moon-worshipping human not pretending like I have it all figured out. And especially when showing up in anti-racist spaces, it feels crucial for me to explore the ways that white supremacy has manifested within myself and my people to erase the radically beautiful Earthly mystical practices that my ancestors have carried with them.

The journey I find myself on is perpetually unveiling the ways that Jewish peoples have and continue to live in alignment with the ecologically regenerative and collectively liberating life I’m seeking to live. I have an inclination that this might be true for everyone– our ancestors know how to be human in ways that nourish us all.

Lila Glenn Rimalovski (she/her) is a playful and prayerful human finding home amidst tall trees, her ancestors, and non-hierarchical land-based community. lila is on a path towards offering herself as a community doula— a facilitator nourishing allied organizations and accomplices in the process of birthing earth-based democratized leadership and rematriating wealth, power, and resources. she is a young, cis, white, Jewish Earthworker currently exploring her second year of making home in the bioregions along the Mohicanituk River, what some call NY’s Hudson Valley.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Good Work Institute or any other agency, organization, employer or company. And since we are critically-thinking human beings, these views are always subject to change, revision, and rethinking at any time. Please do not hold anyone accountable to them in perpetuity.