If we want to act on our longings for a more just world, the first step is to join with others and begin to take part in doing something.

But it is one thing to want to collaborate with others and another to have a clear sense of how to go about it. Enter facilitation, which we define as “the process of making something possible or easier.” I would go further and add that facilitation makes participation and collaboration easier.

In my own facilitation learning journey, I have a sense of re-encountering a set of basics that practice and repeat exposure have helped me understand and integrate at deeper levels. I can now access facilitation principles with more ease and nuance. I want to share some of those basics here.

I think of facilitation design as an act of imagination. Facilitation that is intentionally designed can powerfully impact both the effectiveness and the subtle dynamics of a group’s collaborative work.

Facilitation design can be informed by many different frameworks, principles, and activities; we can draw from and experiment with a variety of approaches. As I have experienced a variety of ways to design facilitated settings, I have noticed that many of the theories, tools, and tips I am drawn to use different words to describe similar underlying intents. It all comes down to participatory facilitation, which is simple but not easy, as the saying goes.

I wrote another post on How to Be a Participatory Facilitator which describes how a facilitator prepares and what types of presence you might want to cultivate. Here, I reflect on what facilitation means to me, and why it is so important to the potential of a group.

Good facilitation is invisible

I like to say that effective facilitation is invisible. In The Workshop Book, R. Brian Stanfield adapts the words of Lao Tzu in this way: “Facilitators are best when people barely know they exist. Their work done, their aim fulfilled, people will say, ‘We did it ourselves.’” Aligned with the idea that the role of facilitation is to enable participation, he writes “the main interaction is between the participants and their ideas…[to] help them process and develop their ideas.”

When a group experience doesn’t go well, it may be the result of poor facilitation. Conversely, when it does go well, it may not be apparent how facilitation led to positive outcomes. One common misconception that trips up facilitators is that the skills required for effective facilitation are a natural or organic expression of the innate personal qualities of the facilitator. But, as I have written elsewhere, the qualities of a good facilitator can be learned, cultivated, and practiced!

In this post, I want to focus on facilitation design, not on the qualities of the facilitator. In my experience, a lot more time is spent designing the gathering than is spent in the gathering itself. That is the key to good facilitation: preparation, clarity of purpose, and imaginative design!

Facilitation is how you achieve the defined purpose of a gathering

The defined purpose of a gathering is the ground from which good facilitation can emerge. In her book Emergent Strategy, adrienne maree brown writes:

There are always a ton of relevant conversations that could happen, but there is usually a very small set of conversations that a particular group, at a particular moment in history, can have and move forward, given their capacity, resource, time, focus, and beliefs. The organizers should have this question at the center of their planning for the event…The goals should be transparent, on the wall, in the room…

In our post on designing a collaboration-ready agenda, we recommend defining a two-part purpose for a gathering. One part is about the deliverables: what the group needs to do, learn, or decide. The other part is about fostering collaboration: what kind of experience we intend to create to honor what group members may be feeling, needing, or hoping, and to strengthen the group.

An agenda or facilitation plan represents the design for how a gathering can flow in order to honor this two-part purpose. It answers the question of how participation can be structured to foster collaboration while realizing the deliverables.

How to get started in designing a gathering

For me, facilitation design is an act of imagination. Actually sitting and visualizing it all helps me get grounded in what’s needed. Here’s how I approach it:

Grounded by a gathering’s purpose, I focus on ideas about how the gathering might flow. I envision the space, people, tools, materials, prompts, timing, transitions, and interactions. I tune into sensing – from my mind, heart, and body – a flow that aligns with the meeting’s purpose and maximizes participation, ultimately documenting the ideas that seem most aligned with the purpose of the gathering. I allow my imagination to guide me, informed by strategies and tools.

There are many theories and tips when it comes to facilitation, and it can even be overwhelming to try and sort through it all. I want to share two structures that have wide applicability to different groups and purposes: Levels of Questions and Affinity Mapping. You can read about each of them in the Tools section below.

And in case you want to go deeper and explore elsewhere, check out the links to a few of our go-to toolkits in the Recommended Resources section at the top right of this page. I encourage you to find a tool that feels relevant to work you’re involved in, and start practicing. Using different tools and being open to new approaches will expand your toolkit… and learning new things is fun!

TOOL: Levels of Questions

One foundational facilitation capacity is to develop awareness of levels of questions and the kind of information each elicits.

In our day-to-day lives, we progress through different kinds of information to get from data to decision and action, or to analyze sources of disagreement. We may do so implicitly or explicitly. Moving through levels of information is an essential skill that can allow us to act quickly in emergencies and efficiently in routine situations.

In Unlocking the Magic of Facilitation, Sam Killermann and Meg Bolger remind us that: “Asking good questions is not only an improv-like “in the moment” skill. Taking time when you’re prepping for the workshop to consider what kinds of questions you should ask, how you should ask them, and what type of learning and answers you’re looking for is essential to asking good questions…The order in which you ask questions can be as important as the questions themselves.”

As facilitators, there is benefit to bringing explicit attention to different levels of information and inquiry, within ourselves and for the group. We often hold our assumptions and beliefs privately, without testing them, and then see our conclusions as “true”. Without an awareness of different levels, we might be leaping across them, without testing our reasoning process or the data that we began with, unaware of what we skipped or missed. We may believe our disagreements stem from differences in the conclusions we arrived at, rather than from differences at other levels, such as seeing the world differently, selecting different data, or having different experiences that cause us to add different meaning to the data we select.

Awareness of levels of questions allows us to:

- bring explicit attention to different levels

- support individuals and groups to think together based on transparent data

- use our beliefs and experiences to positive effect (rather than allowing them to narrow our field of judgment)

- reveal assumptions

- understand sources of difference or disagreement

- avoid jumping to conclusions

- make considered, shared decisions

There are a number of facilitation tools related to levels of questions that I have learned from:

- The organizational psychologist Chris Argyris put forward a seven-level Ladder of Inference model (infographic), which is used by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization.

- Sam Killermann and Meg Bolger use the 5 stages of the experiential learning model in their chapter on “Asking Good Questions” in order to sequence questions: Experience, Share, Process, Generalize, and Apply.

- Liberating Structures’ What, So What, Now What? W³ tool has three levels.

- Technology of Participation developed by the Institute of Cultural Affairs has the Focused Conversation method that uses the same three levels plus an additional “Gut” level, and provides questions that can support a group to focus on each in turn.

Drawing on all these sources, here is my own synthesis of the kind of information elicited by four levels of questions:

- WHAT or OBSERVATIONAL questions allow participants to name the data (facts, reality, sensory impressions, images), to make clear what is being noticed, selected, and considered: What happened? Who was there? What did you see or hear? What facts do we know?

- GUT or REFLECTIVE questions support participants to name reactions and associations from past experiences that influence how we perceive and describe data: Where were you surprised? What was inspiring or hopeful? Where were you engaged or not engaged? What was easy or difficult?

- “SO WHAT” or INTERPRETIVE questions support participants to surface multiple possibilities to interpret what the data means: What is the significance of this? What insights are beginning to emerge? What kind of changes would we need to make? What underlies these issues?

- “NOW WHAT” or DECISIONAL questions support participants to draw conclusions from the data that inform action: What are our next steps? Who will do it and by when? How will we apply what we just learned?

You can view or download a visual of this approach here.

As we develop an awareness of these levels, facilitators can support a group of participants in moving through a journey together in a way that is in sync with what our brains consider when moving from data to action. The levels of questions approach can be used to design the arc of a gathering, to develop prompts for moving through an agenda item, or to listen to where a group’s conversation is and notice what might be needed next.

TOOL: Affinity Mapping

There is a design thinking concept I’ve encountered that is simple, but powerful. True to the tools used by many design thinkers, it is often visually expressed and we talked about it in our post Accountability is a Form of Support. This is the concept of a process that moves from uncertainty and complexity to clarity and decision-making.

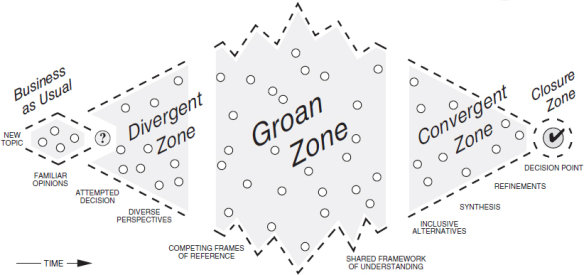

As we’ve discussed, moving as a group from a topic (point A) to closure or a decision (point B) is a process that involves struggle, uncertainty, and iteration, to eventually discern patterns and insights, and then to reach clarity. Another way of describing this process is that we must journey through three zones:

- First Zone: Starting from point A, the first zone is divergent—get open, go wide, push boundaries, invite unexpected ideas.

- Middle Zone: The middle “groan zone” presents the opportunity to struggle and explore how ideas can combine and insights be discovered.

- Final Zone: To progress to point B, the final stage is convergent—organize and choose the ideas to move forward.

Focusing attention on this inherently messy process is a way to increase our comfort with struggle and uncertainty as we move through that middle zone to get from A to B.

Affinity mapping is one approach for getting from A to B by visually moving ideas around and organizing related ideas into distinct clusters. Originally devised by Jiro Kawakita in the 1960s, this process is also known as affinity diagramming, collaborative sorting, snowballing, card sorting, a consensus workshop, or the KJ Method.

Describing the Affinity Map tool in the book Gamestorming, David Gray writes: “Brainstorming works to get a high quantity of information on the table. But it begs the follow-up question of how to gather meaning from all the data. Using a simple affinity diagram technique can help you discover embedded patterns in your data (and sometimes break old patterns) of thinking by sorting and clustering language-based information…[and by giving] us a sense of where most people’s thinking is focused.”

We share a simple way to get started using this approach. We use post-its to gather ideas, with one idea per post-it; then we cluster them in like piles. Finally, we take time to name those clusters, which often allows us to see things more clearly, having completed the journey from A to B, as a group.